January, 2015, New York

Royal Collins announced that the company will cooperate with American Collective Stand (ACS) who is the operator of BEA New Title Showcase project at 2015BEA. The New Title Showcase is an official exhibit at The London Book Fair and Bookexpo America. It is a low-cost way for any publisher to have their titles-both print and digital-on display at major international book fairs and at prime exhibiting locations. Official exhibits mean high visibility, promotion and traffic, and will help drive the audience, including book buyers, publishers, agents, media, librarians and more to your books and ebooks. The New Title Showcase is a partnership between Reed Exhibitions and The Combined Book Exhibit, a company of ACS.

To learn more, please read the following link.

http://www.newtitleshowcase.com

“New Title Showcase (NTS) offers a great opportunity for all of our partners in Asia, especially so for our China-based clients this year. As the featured, guest-of-honor country for BEA 2015 in New York, we anticipate a good number of exceptional new titles from China will be displayed in the NTS area,” said Mr. Stephen Horowitz, Chief Editor at Royal Collins. So far, at least twenty-five new Chinese titles will be on display at NTS for BEA 2015.

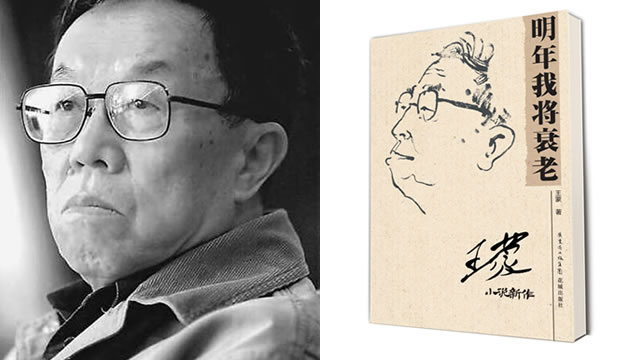

Recommendation Title

I’ll Be Old Next Year

Wang Meng’s latest publication is a collection of seven short stories, written over the past decade, that address issues of age, memory and loss, in tones that range from sorrow, to rage, to tender irony. The stories are rooted in the traditional culture of places like Taiyuan and Beijing, and in the distant pasts of characters now grown old, but their branches extend around the world, and bear blooms in the present day.

About the Author

Wang Meng’s story is unique among Chinese writers. Born in 1934 in Beijing, he began life under Japanese occupation, and as a young man became an ardent supporter of the Communist Party and the Chinese revolutionary cause.

The short story “A Young Man Comes to the Organizational Department,” published in 1956, nearly ended Wang’s literary career before it began: its critique of bureaucracy was interpreted as an attack on Party authority. It wasn’t until the story came to the attention of Chairman Mao himself, who praised its rebellious spirit, that Wang was assured of a career, and a reputation.

In 1963 he applied to be sent to Xinjiang, amid a general enthusiasm for re-connecting with rural society – he had long been told that his writing was too intellectual. He and his family would eventually spend sixteen years living and working in Yining, near the Khazahstan border, during which time he learned the Uighur language and became familiar with local culture. The experience left a profound mark on him as a person and a writer, and much of his most important later writing draws on his experiences in Xinjiang – most notably the short story “A Pair of Grey Eyes,” and the novel “The Scenery Around Here.” It also confirmed for him the importance of fiction grounded in real experience and real people, and while his literary voice bursts with lyrical creativity, his stories grow from close observation of life.

A year after the end of the Cultural Revolution, Wang and his family returned to Beijing, and to acceptance in literary society. Throughout the 80s, as enthusiasm for culture and literature steadily mounted, Wang’s cachet continued to rise. He was gradually promoted within the China Writers Association, and finally was made Minister of Culture in 1986. He lasted three years in office, before quietly stepping down in late 1989, a year that also saw the publication of his seminal short story, “Tough Porridge,” an allegorical commentary on reforms.

The light, ironic tone of that story characterizes much of Wang Meng’s writing, particularly that produced since the early 90s. Humor and self-deprecation come easily to him, something he attributes to the influence of Uighur culture, but surely also stems from the staggering range of conditions under which he has lived and written over his long life.

Now, after more than six decades of writing, during which he produced six novels and countless novellas and short stories, Wang Meng is looking back over his personal and literary lives, full of memory, love, writing and passion. At the age of eighty, Wang Meng shows no signs of fatigue. He has the energy of a man of forty, and the passion of a man of twenty.

More than a dozen of Wang Meng’s short stories have been translated and published in English, notably several pieces in the collection Loud Sparrows, published by Columbia University Press in 2008, and in The Stubborn Porridge and Other Stories, published by George Braziller in 1994.

About this Book

Totl 241 pages

• Autumn Fogs (秋之雾), 39 pages

• Taiyuan (太原), 28 pages

• Suspense Amid the Brambles (悬疑的荒芜), 36 pages

• History in the Hills (山中有历日), 36 pages

• The Love Song (With Variations) of Mr Moustache (小胡子爱情变奏曲), 44 pages

• A Still Garden (岑寂的花园), 36 pages

• I’ll Be Old Next Year (明年我将衰老), 22 pages

Autumn Fogs

In the depths of his sleep, Ye Yuanshi heard a sound. Was it a knocking on the door, or the rustling of the person next to him? Was it a soft sigh, or a moan of deep feeling? He didn’t feel like waking.

But he was also a little afraid: What if he never woke again?!

It gradually became a crying-out: the sound grew stronger, but somehow not louder – was something weighing down his limbs? Who’s voice was that? Strange and yet familiar; close and yet distant; secretive and yet resolute. Like something from the ancient past; like something fallen in a well. He dragged, he thought, he fought, and yet only went deeper down, unable to pull himself or anything else out.

“I’m not telling you.” “I won’t say.” That was a playful and flirtatious way of talking. If a woman spoke to you that way, it meant she was already in love with you.

In the end, perhaps it was the watchman striking the hour, a sudden north wind in the night, that had suddenly awoken him from his sweet sleep? The weak yet penetrating whistling whine combined with the fluttering rustle outside his window to unsettle him. Could it be true that he had forgotten those very things he should never have forgotten about his past?

Ye Yuanshi decides, in his advanced old age, to accept an invitation to return from America to his native China, and revisit some of the scenes of his youth. He is returning to Peach-Blossom Village, in an area once famous for the Peach-Blossom style of folk song, an art-form that now survives only thanks government-sponsored cultural-preservation efforts. As Ye Yuanshi’s driver takes him deeper into the mountains, thick autumn fogs envelop the car, and Ye loses himself in a haze of memory, where his long-lost wife is awaits him.

Taiyuan

It’s springtime, and he pushes a wheelchair out on the streets of Taiyuan.

His hair is speckled gray, his bearing upright, his spirits high. She in the wheelchair has a head of perfectly silver hair, and she has made herself up so carefully, so beautifully, so elegantly, that even as you glance in sympathy at her wheelchair, you’ll find yourself taking another glance at her. Her features are lovely, and perfectly proportioned – there is a particular beauty about her nose and mouth. She is happy, in the main, and that serene smile, that seems to have traveled across the depths of suffering, is more affecting than any easy laughter.

Seeing them this way, you could imagine, you would guess, that they must have had beautiful youths.

Taken together, their ages add up to more than one hundred and fifty.

They talk continuously, but in seemingly broken sentences: could it be that Chinese is not their native tongue? Their voices are good, though; the man can sing bits of Pavorotti’s “O Sole Mio” and “Torna A Surriento”, while she hums, indistinctly, Barbara Streisand’s “Woman in Love” and “Memory”, the theme song from Cats. Her songs may be more charming for being indistinct.

More precious than any pop melody, of course, are the Hubei folk song “Cei-Dong-Cei”, and the high song of the Shanxi bangzi.

But what could those things have in common?

The story begins with the tale of Liu Xia and Lang Nuoyi on their first trip together to Taiyuan, in Shanxi province, in the mid 1950s. The first time Lang Nuoyi heard Liu Xia’s voice, she was reciting his own poetry on a local radio stations – he wrote her a letter that very night. Their relationship is nourished by the songs of Shanxi, by local culture before it was diluted by modernism and Mandarin Chinese, and by youthful ambition and naïvete. Fifty-two years later, the songs have faded from memory, but some flames still burn.

Suspense Amid the Brambles

By rights, December 8, 2008, should have been a happy day. The sky was clear, the air bright and full of vigor – you felt a “zing” from the moment you opened your eyes. It had been a very, very long time since old Wang had had any real reason to be unhappy. A visiting friend had once said to him: you’ve got in made in every way; what more could you want!?

He’d agreed to do an English-language interview with CCTV9, a special program in honor of the upcoming 3rd Plenum of the Community Party, and one that would also include a discussion between Wu Jianming, Long Yongtu and He Zhenliang. He’d done one practice round with the host, Ms Tian, and the results had been better than expected. At his age, he still liked to take on new challenges. He couldn’t quite shake the secret desire to show off a bit. His English skills were mostly the result of self-study, starting at the age of forty-six; the year before he’d traveled to Russia to take part in the closing ceremony and book fair of the Chinese Language Year, and he’d spent three whole months learning how to sing the Soviet song “Distance, Oh the Distance!” in the original Russian. Though in conversation he wasn’t able to make his tongue curl around the Russian syllables, in song his accent was entirely passable. At the Moscow book fair, an announcement was made about the publication of a collection of his fiction, a collection of criticism about his works, and an essay collection containing some of his essays, all translated into Russian. Sample copies were already out of his newest work, Some Help from Lao Tzu, and the Xinhua Wenxuan Group had already decided to do special promotion for it in 2009. The heavy smogs of a few days ago had dispersed, and the pollution indicators had fallen from 400 to 40. That morning he’d received an email linking to a bit of online news: a website had compiled a list of the top-earning authors of 2008, and he’d come in at number 24. He seemed to recall that, two years ago, he’d been number 12. Of course, talking about your earnings as a writer was as ridiculous as a high-heels on a pig.

In perhaps the most autobiographical piece in the collection, Wang Meng addresses his reputation as a writer in China, the ways in which that role has changed over the decades, and his conflicted relationship with the public.

The story begins with a break-in at his house. As the minor mystery develops, it is bound up with Wang’s observations of his famous, wealthy neighbors in the housing complex where he lives. Who is the mysterious female poet living all alone in one of the houses? What are the roots of the feud between two irreconcilable neighbors? And why does the poetess so suddenly disappear?

History in the Hills

Old Wang’s notice had been attracted to nothing in the mountain village so much as a particular young girl, around nine years old, and not too tall. Her eyes were big and lively, and so black they seemed to pierce you. She wasn’t large, but there was a solidity to her, and she had an air of tautness, as if she were perpetually on the verge of flight or attack. She’d once put on lipstick and a pair of old high-heel shoes, wobbling from side to side as she walked. When she spoke, she smiled with complete abandon. Sometimes she joined in the conversations of adults, talking about the old tofu-maker Guo, who lived in Snail valley in the mountains, how his son was a little soft in the head and still hadn’t found a wife, though he was past the age of thirty. There was no other girl, in all of old Wang’s childhood, who had been so happy and thoughtless, so able to laugh and converse with adults as equals, and speak on any topic that came into her head.

The girl is Bai Xing, and in the decade or more in which old Wang stays in her village, he sees her grow from a feisty child into a hesitant young woman. In this small masterpiece of characterization, Wang Meng teases apart the complexities of youthful hope and mature resignation, deftly portraying the tension between Bai Xing, her father, and her step-mother, and her struggle to balance her own aspirations against the demands of family.

The Love Song (With Variations) of Mr Moustache

The news that Mr Moustache had hooked a massive carp, pushing ten kilos, spread instantly through the whole Zilizi valley area. They said that the fish showed itself while he was bathing (ie swimming), but when he went after it he not only failed to catch it, he drank no small quantity of riverwater, and nearly ended up at the bottom to boot. From that moment on he was determined to get it on the hook, and to that end bought no less than ten kilos of beef as bait, mixing it by hand with fish-attracting flavorings. Mr Moustache went to cast his hook no fewer than nine times, spending countless hours, before he finally achieved his aim of hooking the fish on his long line.

He hired the cook from a home restaurant at the edge of his village to make their specialty: “blanched carp”. First marinaded, then boiled. Then you made the topping, and spread that piping-hot, rich, fragrant, salty topping all over the fish. This was the end of the last century, and incomes were limited in our little mountain village, yet Mr Moustache went to such great expense in putting on this banquet, even inviting old Wang along, an as something of an “honored guest”, no less, seated at the head of the table… Many Chinese look askance at the Western tradition of putting the host at the head of the table, while the guests are seated to either side. But perhaps the size of that carp caused old Wang to re-evaluate his impression of Mr Moustache. Not to mention that glorious, alluring, swoon-inducing bowl of toppings…

Mr Moustache has problems: he knows this is the era of opportunity and ambition, he’s just not quite sure how to take advantage of it. Over the course of the story he tries almost as many professions – shop-keeper, taxi driver, local government – as he does wives and girlfriends, but nothing quite seems like a good fit. In this allegory of contemporary society, Wang treats the Chinese self-made man with gentle mockery, and real compassion.

A Still Garden

All these houses seem to have popped up overnight. Them, and the lake and forest beside them. They grow like a clutch of illegitimate children. Before, there was only a stretch of old mud here, full of skewed, toppling rushes, and surrounded by willows, some of them rotting with their roots submerged, others with lush green crowns. They say the mudlands had produced countless frogs and turtles. According to Chinese tradition, one could think of the mud itself as having given birth to the frogs and turtles. They said there was an unusual connection between those frogs and those turtles, so much so that the frogs would sit silently on the logs, voiceless and frigid, while the turtles suddenly bulged their throats in belligerent, protesting calls.

Even the real estate agents couldn’t explain the provenance of the villas or their parents’ identities, nor could they explain the connection between this luxury housing estate known as “Lake-Gull Villas” and the frogs, turtles, waterbirds, and mudlands. Very few now alive had ever seen those lake gulls before this area was designated a nationally-protected wetlands. The luxury villas that leapt out of nowhere were even more unlocked for. No one could produce their birth certificates, or proof that they had not violated the One-Child Policy: they had no housing registration. You’d be forgiven for doubting the legality, the trustworthiness, even the propriety of their existence. But sure enough, after the area was given the lofty title of “Lake-Gull Villas”, and the wetlands were nationally registered and protected, the most immediately-obvious change was the re-appearance and congregation of lake gulls. The gulls seemed to follow their own name – proof of the ancient concept of “man and nature in harmony”. The gulls flew in flocks and clouds, swooping carelessly down over water and road alike, sometimes landing on the sand flats or the little island, until the people who came to fish started to complain of them. Perhaps it was the fish they were jealous of.

The great mystery of old Wang’s housing complex is the estate with the beautiful garden, owned by a man no one has yet laid eyes on. At last two women – a painter and a writer – get a glimpse of half the man’s face, and both swoon on the spot. Upon recovery they are moved to creativity, and the bulk of this piece is penned by the writer. She tells the story of the mysterious master of the garden: his personal history, his travels abroad, his love affairs, his family, and finally his daughter, who after many years has come home to find her father.

I’ll Be Old Next Year

I know that within all of this there are your thoughts, your hopes and help, your smiles and tears, your breath that even until the last was still light and even, still gentle and prim. We have reached the autumn of 2012, this ruthless and terrible year. Visiting the gardens next to our home, the leaves are deepening from yellow to red, as though painted, or soaked in dye, the crimson gradually spreading, bright yet also heavy. They suffer waves of wind and rain, each more chill than the last. The so-called red-leaf season has begun with the first fall of frost, and the road to the Fragrant Hills is thronging – most people’s impression is that the visitors are more numerous than the trees, and that one ends up looking at black-haired heads instead of the round blushing leaves. There may be some things missing from this great land, but the heat of bodies and the clamor of voices are not among them.

The final dream-like prose-poem in the collection finds Wang meditating on his own youth, and everything that has changed since his early days of idealism. As the story’s heat grows more intense, Wang’s discussion of the gains and losses of old age, his acceptance of age but insistence that he is not yet old, begin to thin and fray, eventually revealing the story for what it is: a love letter to his long-lost wife.